Audio Editors: Sometimes, you just have to do your best

I was once asked if I could add in the end of a sentence during an episode edit.

The tape was recorded during a live event and the speaker had moved their mouth away from the microphone while addressing the audience. Whatever the audience got to hear, the microphone didn’t pick up, and those words were lost to that room.

I had to gently reply that I couldn’t edit in audio that I didn’t have. Short of having the speaker re-record their sentence after the fact, there wasn’t much that I could do.

Vocal Fry Illustration

The cut at the beginning of the piece was a little awkward as a result. I’m sure someone listened to the final product and assumed I had made a huge editing blunder, but that doesn’t keep me up at night.

I did my best with what I was given—within the time I had allotted—and based on the pay that I had received.

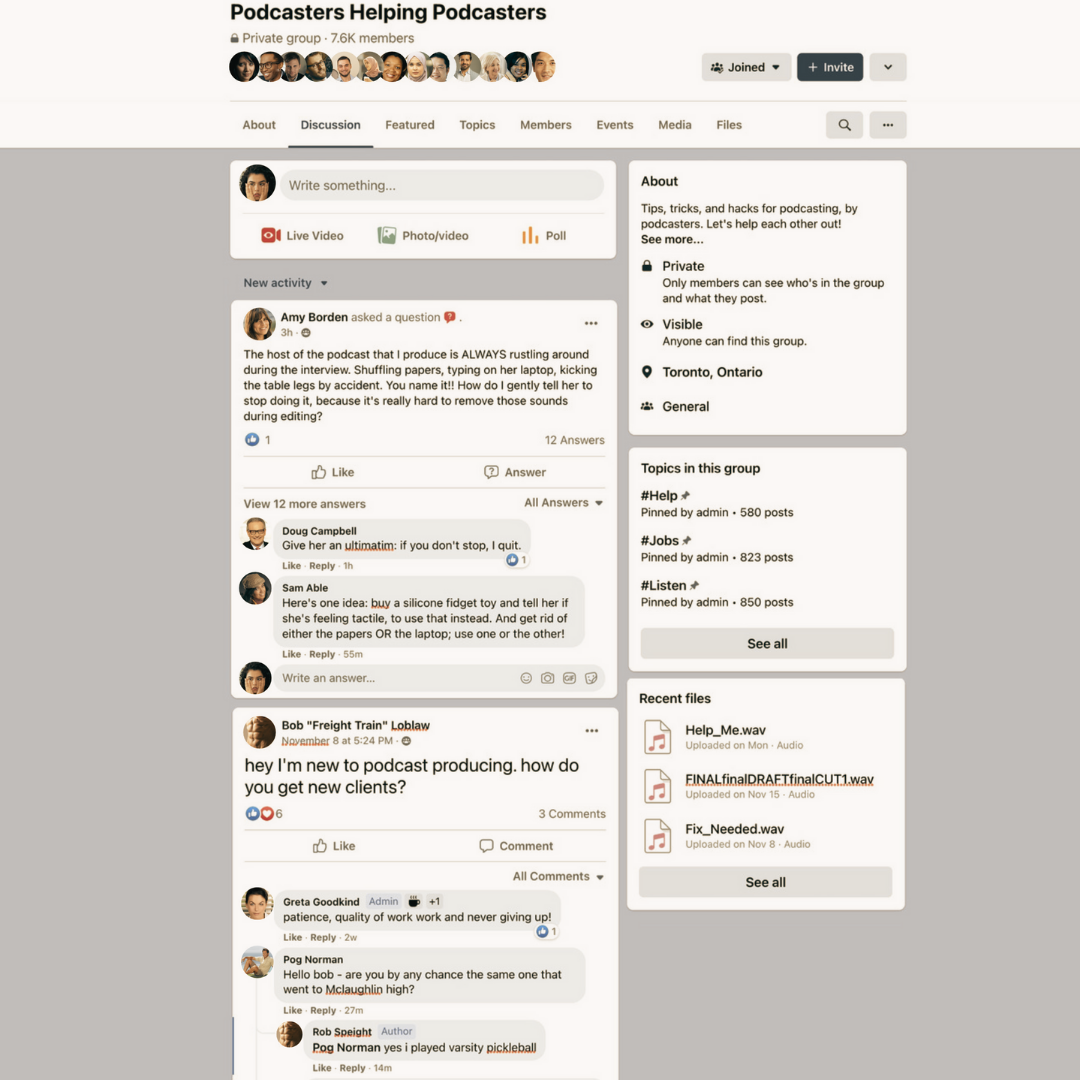

Similar scenarios pop up in the editor community groups that I’m a part of.

I noticed a curious trend of members crowdsourcing ways to tactfully request that their clients not credit them as editors, and not recommend their contributions to the show as examples of their work.

These were generally editors with no other hand in the production process. But, that’s the very thing that made them shy away from claiming their work — errors in the production process that produced subpar audio.

Let’s talk about materials...

Unless you have control over the whole production process, you’re sometimes given material that’s not your gold standard. You may find yourself combing through issues that could have been adjusted earlier like:

A host with poor microphone technique or a poor set-up.

A barking dog in the background.

Guests constantly hitting the table, chewing, palming a basketball, or otherwise making disruptive sounds that are tedious (or impossible) to edit out.

As an editor, it’s your job to bring the audio together and that tends to include clean-up. However, you’re still entitled to place limits and set expectations on what you realistically can do given the parameters of the project or the quality of the tape.

It’s best to be upfront and honest about what you can do with what you’ve been given. Promising that you can edit an hour-long street interview, done in the middle of the city during rush hour, to sound like everyone was recorded in a professional studio—for $50, under a rush deadline—is only setting your client up for disappointment (and yourself up for immense stress).

Wait, did we forget about cost?

The truth is, sometimes errors are left in the final recording because a client didn’t have the budget for a more intensive edit. More often than not, the editor is fully aware of the audio glitches.

But audio repair takes time, much more time than it would take to adjust the recording conditions in the moment for better sound quality. Many clients don’t understand the labour it takes to fine-tune every bark, siren, or moment of choppy audio.

So instead of disparaging an editor for letting an episode go up with extra noise, consider whether they would have been compensated for the additional work to fix those elements.

After all, what should an editor on a shoestring budget be expected to do with:

A booked and busy guest who took the interview in the back of a cab complete with the soundtrack of a bustling city?

A broken or lagging hour-long Zoom recording because someone had poor internet access?

Or an unintelligible voice muddied by a decades old headset that was briefly the dog’s chew toy?

If you’re new to editing, a lot of this is trial and error. As you work on more projects you’ll learn which requests are realistic, which would require an entire production company, and how to gently set expectations. Sometimes you’re given material that isn’t all there, and you’ll have to do your best to put it all together, even if it’s not immaculate.

And that’s okay.